It is I who have climbed the highest mountains,

To the remotest parts of Lebanon,

And have cut down its loftiest cedars,

Its choicest cypresses,

And have reached its remotest lodge,

Its densest forest1

A Documentary of Lebanon’s Pain

In Charles Glass’s 1989 documentary Pity the Nation,2 he laments the tragedy of Lebanon’s descent into a civil war that appeared to go on without cause or end. In a war where various mercurial factions could change loyalties on a dime, this sense of the war—which would end the year after the documentary’s first airing—certainly had some merit. Glass, himself of Lebanese descent, masterfully gives the audience a sense of what Lebanon (or at least Beirut) was like before the war—serene, diverse, prosperous, on the move—and he does touch on the old-time hallowed traditions still practiced in the Christian mountainous regions of the country. He beseeches his audience to take pity on this poor country and its people. Indeed, the title of the documentary is a nod to the poem by the Lebanese writer Khalil Gibran, which bears the same name.

While Charles Glass’s Pity the Nation powerfully captures the emotional devastation of Lebanon’s civil war, it falls short in explaining the underlying causes. This two-part essay series seeks to move beyond pitiable lamentation to explore the complex political, religious, and social dynamics that continue to shape Lebanon today. The first essay will be dedicated to assessing dynamics in Lebanon until the civil war’s outbreak in 1975. The second will aim to explore Lebanese politics during and after that traumatic war.

Let us, however, first linger on why the documentary possesses both strengths and shortcomings. The documentary mimics the sense of dread and prophetic yet opaque tone of Gibran’s memorable poem—written and published long before the terrible war:

Pity the nation that is full of beliefs and empty of religion…

Pity the nation that acclaims the bully as hero, and that deems the glittering conqueror bountiful…

Pity the nation that raises not its voice save when it walks in a funeral, boasts not except among its ruins…

Pity the nation whose sages are dumb with years and whose strongmen are yet in the cradle.

Pity the nation divided into fragments, each fragment deeming itself a nation.3

The lines evoke a sense of sectarianism, hollow beliefs, and divisions that destroy or render impotent this benighted nation. Yet, while the poem—and indeed the documentary—captures this sensation well, there is no in-depth exploration of the causes behind the Lebanese Civil War. There is a strong emotional atmosphere, but little clarity. Glass describes the conflict and violence as madness—a word that distances rather than explains.

After all, one cannot understand madness. It is as if blind, idiot Chaos came down drunk from the void and was let loose upon Lebanon during those years, leveling all causes into meaninglessness. For example, Glass fails to truly explore what ideas or pressures motivated people to take up arms in the first place. The question of why the Israelis bombed Palestinian areas of Lebanon is never answered. He shows the aftermath, and his Palestinian friend speaks about it, but the rationale behind Israel’s actions is absent. Glass briefly mentions Palestinian terrorism, but does not go into detail. The emphasis remains fixed on what his friend experienced in the bombing raid. “My life is a form of terror,” his friend tells him.4 One can certainly sympathize with the man and his experience, but ultimately, this tells us nothing about the big picture at play.

There is, then, much obfuscated in Glass’s lyrical lament of the Lebanon that was and the Lebanon it has become. While the Lebanese Civil War ended in 1990, its causes, trauma, and aftereffects continue to resonate to this day. The conflicting nature of the identities of its people is worthy of exploration—not only with regard to how they shaped the divisions behind the Lebanese civil war, but in terms of their continuing reverberations. It is with this hopefully enlightening task in mind, that I seek to do some justice in these essays.

Lebanon: The Mother Of Many Children

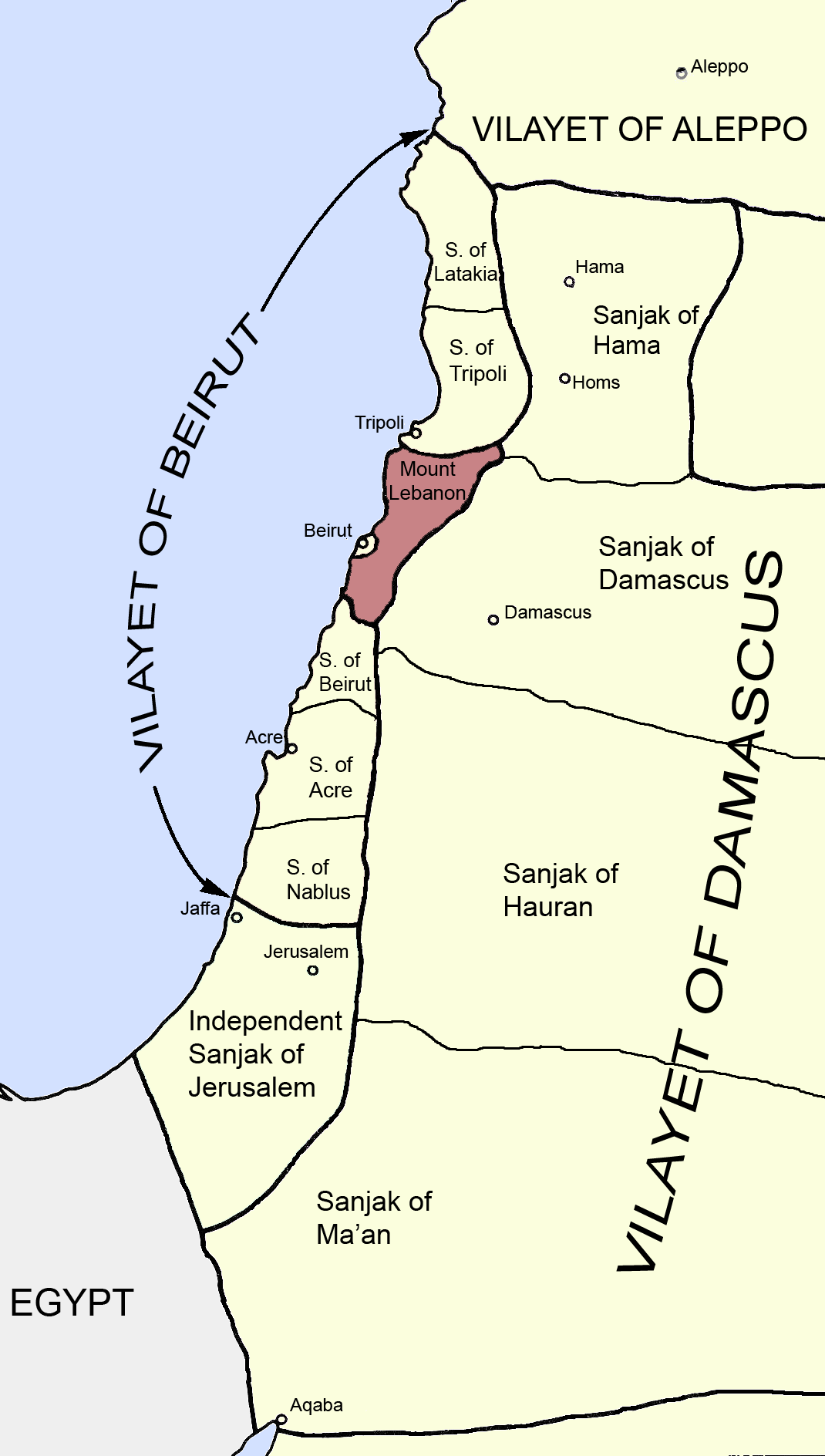

The land was pregnant. It gave birth to many children. Maronite Christians, Druze, Sunnis, Shia, and others made Lebanon their home. Long gone were the haughty glory days of old. The city-states of Canaan and Phoenicia5 had long been eclipsed—reduced to the lingering dust of legend. Their last independent remnant on the native soil—the city-state of Tyre—was rendered into ruin by Alexander the Great—the Hellenes’ chosen, all-conquering son. Baal and Astarte had been dethroned and superseded. Empires came and went. Now, Christianity and Islam ruled the hearts of the masses. It came to pass in the early 19th century, in the days of the Ottoman Empire, that American Protestant missionaries first set foot in Lebanon—and began a process that would deliver children of another kind.

These missionaries developed a passion for Lebanon—then a district of Ottoman Syria6—Beirut, and its peoples. Jerusalem might have held the formal title of “the most glorious of postings” by dint of its hallowed history, but she had been reduced to “a cold and stony Turkish provincial rathole.” Beirut, by contrast, was “a modernizing harbor town with a gem-like climate and lovely, European-like mountain scenery.” Both the British and American missionaries in this outpost of civilization came to sympathize with the local Arabs in their plight against the Turkish tyrant.7 This is not to write that these missionaries fell in love with all the locals. Their attempts to convert the Eastern Christians to Protestantism led to troubles with the Greek Orthodox and Maronite churches.8 The Maronites, followers of a fifth-century saint, late associates of Catholicism, and friends of France, would eventually become particularly bitter adversaries to the zealous foreigners. For at this same time, the Maronites had already begun to develop “their own nationalist ideology” and were, atypically for other Syrians, “on their way to becoming a modern people.”9 Thus, while the Protestant missionaries regarded the Greek Orthodox in adverse religious terms—as idolatrous relics of the “corrupt East,” their strained relations with the Maronites took on additional baggage.10

The Tale Of Two Schools

When the Protestant missionaries realized that their labor was not rewarded with mass converts, they elected to take on a civilizing mission to Syria. They would substitute religious revelation with “Western education” as the idea they would sell to the masses.11 They envisioned “a nondenominational college, open to all races, and run on New England’s best standards” as their dynamic contribution and stamp on “Syrian culture.” The college should therefore reflect and improve the local environment. As such Arabic—not English or French—would be “the language of instruction.”12 Their efforts were crowned in 1866 with the opening of Syrian Protestant College—later renamed The American University in Beirut (AUB)—that would do just this.13 The missionaries’ choice to teach in Arabic was a vital one as such educational programs were pioneering ones and in the words of George Antonius, a Christian Arab nationalist author, “marked the first stirrings of the Arab [literary and national] revival.”14 “The College…helped give birth to Arab nationalism, and allowed Arab nationalism to develop. You could almost say that Arab nationalism grew up out of the College,” noted the great-great-grandnephew of the board of trustee’s president.15

Yet, Arab nationalism was not the only ideological movement born on Lebanese soil. In 1874, the French Jesuits moved a school to Beirut and named it Jesuit College—the school would then be renamed twice over to the French University, and then to the French University of Saint Joseph.16 It would be the rival to AUB not just academically but in terms of its vision of Lebanon:

Saint Joseph emblemizing the intellectual and ideological heart of a Lebanon that saw itself as French, Maronite, Christian, pro-Israeli and Western, a Lebanon that claimed descent from ancient Phoenicia and looked down upon—spat upon even—the Arab Moslem masses; AUB, on the other hand, became the heart of an Arab nationalist awakening that viewed Lebanon as an integral element of Syria and the wider Arab world, a world for whom the State of Israel was a provocative remnant of British colonialism, just as Maronite-dominated Lebanon was a remnant of French colonialism.17

The foreign missionaries became the midwives of the modern sense of Lebanon and its ideological poles.

We should, however, take care not to oversimplify matters. It would be Negib Azouri, a Lebanese Maronite and Ottoman official, who in 1905, would be the first to suggest that Arabs secede from the Ottoman Empire and predicted that Arab nationalism would be in contention with Zionism.18 He called for a version of Arab nationalism that would separate religion from the state and wanted it to “respect the autonomy of the Lebanon, and the independence of the principalities of Yemen, Nejd [a region in Saudi Arabia], and Iraq.” While he offered the throne of this “Arab Empire” to a member of the ruling dynasty of Egypt who favored this project, he expressly excluded Egypt as part of the Arab nation due to its geography, distinct racial composition, and the legacy of a pre-Islamic language unrelated to Arabic.19

The French Mandate and Demographic Engineering

The aftermath of World War One and the breakup of the Ottoman Empire changed the face of the Middle East. By then Lebanon proved to be the fertile mother soil of many ideological movements of import to the region. Phoenicianism,20 Pan-Arabism,21 and Greater Syrian nationalism22 found roots there. Maronites became torn in their lobbying in France over whether the Lebanon they envisioned should have expanded borders at the cost of demographic imbalance, or a smaller, yet more demographically uniform Catholic-majority Lebanon.23 The concept of Lebanism was created to facilitate the former territorial and demographic arrangement. This identity sought to paint over the divisions by advocating pluralistic Lebanon that included space for the “non-Catholics and non-Christians.”24 Even in such arrangement, however, the Maronites and other Catholics expected to dominate the country politically.25 Phoenicianism made a similar pitch through its conceptualization of a unique Lebanese identity that was not steered by modern confessional divisions.26

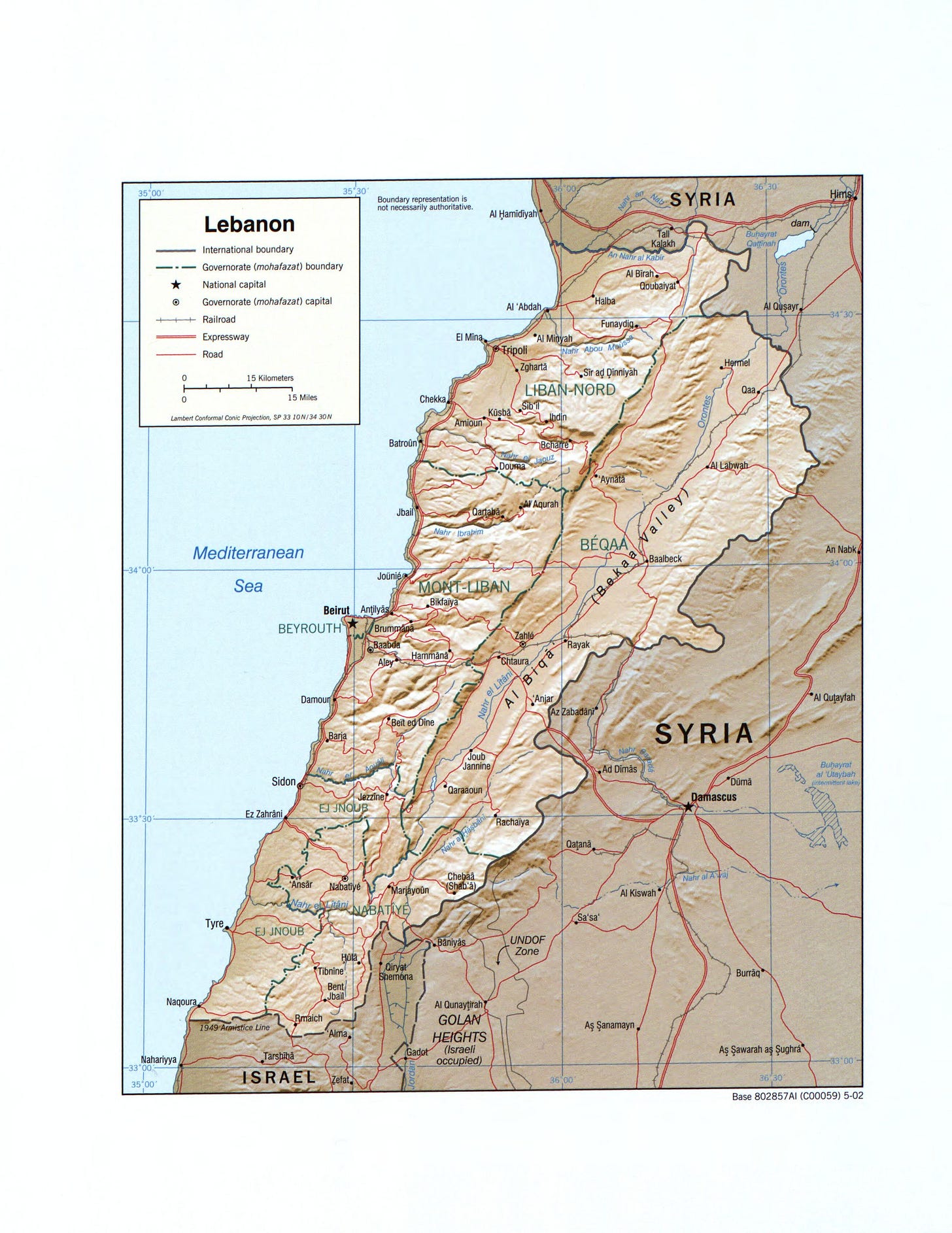

The European imperial powers effectively carved out Lebanon from the land had promised to Faisal bin Hussein, the prominent leader of the Arab revolt against the Turks.27 Even so, among the Sunni and Shia communities in Lebanon there was vacillation “between the French and Faysal” in 1920. Faisal, by then, had set up a rival government to the French in Syria, which would soon be ousted and the French would thereby gain Mandatory control over Syria and Lebanon.28 Pro-Faisal Arab nationalism proved to be confined in Lebanon to a “small intellectual class, camp followers of the Sunni Sulh family and the Damascus activists.”29 In the end, the French drew the borders of the country according to the vision of Greater Lebanon, all while “assuming the supremacy of confessional identity” among its disparate peoples.30 Yet, as the attentive reader will have already noticed, it was not only the people who were disparate, but also their ideological visions of Lebanon: whether as a distinct national entity or as part of a broader Arab or Syrian identity.

Formation of Modern Lebanon: 1921-1946

This French decision had major repercussions. A 1921 census conducted by them showed the demographic consequences of a Greater Lebanon.

65 percent of the population of the annexed areas was non-Christian. The overall Christian majority changed from 80 percent in Mount Lebanon to 55 percent in the new Lebanon. Maronites remained the largest community but their proportion almost halved, from 58 percent to 33 percent. Courtesy of the annexed areas, Sunni Muslims were up from 3.5 percent to 17.2 percent, even with some boycotting the French census, and Shia increased from 5.6 percent to 17.2 percent.31

Despite these demographic shifts, the Maronite church, its patriarch, and the majority of the Maronite political elite refused to consider any other alternative to Greater Lebanon. Emile Eddy, a Maronite politician, stood almost alone among his peers in protesting this plan. He preferred “a proper Christian Lebanon” to the “multicommunal mélange” it would become as Greater Lebanon. Yet, Eddy’s peers convinced themselves that Christian émigrés from Lebanon would return and that an influx of Armenian Christian from Anatolia would only swell their numbers. Furthermore, even with the demographic composition as it was in 1921, Christians still had the majority in political representation and Maronites secured their role as the leaders of this new Lebanon.32

The Sunnis, now the second largest community in this new Lebanon, “repudiated the new entity and pressed reversal of the annexations.”33 The Shia—who had little political coherence during this period—ended up supporting the new arrangement when the French awarded them state recognition of their religious court system in 1926.34 The Druze were initially split on the proposition. The Great Syrian Revolt of 1925 bled into certain Druze communities in Lebanon who greeted the rebels eagerly. Yet, major Druze families and communities saw the danger in alienating the Maronites and French and remained distant from the rebellion. These Druzes appreciated the opportunity of “a distinctive Lebanon” and “had accepted the Christian advantage.”35

The French replicated the Christian-dominated political system of Mount Lebanon in its creation of the national confessional democratic character of the new Lebanon in 1922. This national system reserved for the Christians 17 seats and for Muslims and Druze 13 seats. Elections would be in two-stages and universal adult suffrage was granted.36 They then ratified the borders of this state-to-be based on the Greater Lebanon parameters in the Mandate’s constitution in 1926.37 Emile Eddy’s crusade for a lesser but more Christian Lebanon that would jettison “the annexed [non-Christian] areas” with the exception of Beirut had failed.38 Eddy, among other ambitious Maronite politicians, however, switched to promoting Phoenicianism in their quest for national office.39

The Role of Education and Ideology

The Lebanese education system would influence the development of its politics. Saint Joseph “produced lawyers, by far the leading profession among Greater Lebanon’s politicians,” such as the “upper-class Sunni Arab nationalists.” AUB, the alternative to the Catholic university set by the aforementioned Protestant missionaries, by the 1930s became “a hotbed of radical politics.”40

Radical politics in the Arab world, in addition to its various nationalist designs, during this period was fascinated by European mass political movements such as fascism and communism. The Great Syrian Revolt of 1925 demonstrated the potential of nationalism as a mass movement for Arabs, more so than the 1920 attempt to secure Faisal’s throne in Syria.41 The intellectual Hussein Aboubakr Mansour wrote about those formative interwar years that “communist, Arabist, Egyptianist, Syrianist, and Islamist groups proliferated and created an ideologically competitive mimetic contagion” in Egypt and the Levant that used these abstract ideas of European thought “along with the local symbols of Islam and Arab culture and altered the entire substructure of Arab thought.”42

He added that:

Nazism and fascism served as an inspiration and a prototype to many aspiring movements such as the Syrian Socialist National Party and the Muslim Brotherhood. The excitement in the prospects of a German victory brought, along with Arab intellectual affections to German philosophy, can be clearly read in almost all the memoirs of those who came to political age during the period including [Egyptian] Presidents Nasser and Sadat in Egypt and Antun Saadah in Syria…During the [Second World W]ar, the minority of Arab intellectuals and thinkers who firmly opposed Nazism and fascism belonged to either the older generations of the pro-British or else were young communists. Otherwise, it is not an exaggeration to say that the overwhelming majority sympathized with Germany and the Axis and encouraged the population to do so. The political fervor of the time was primarily anti-British, anti-French, and anti-Jewish, and in favor of revolutionary mobilization; the question of ideology was secondary at best.43

The Syrian Socialist National Party (SSNP), a promoter of Greater Syrian ideology along totalitarian lines, is particularly noteworthy here is it was founded in Beirut in 1932. It later became a junior political ally to the Ba’athist regime in Syria under the Assads.44 Saadah, the founder of the SSNP, was a tutor of the German language at AUB during its formation.45

The 1930s turned out to be a fateful decade for Lebanon. At Sunni instigation, the French would conduct a second national census in 1932. This turned out to be the last census conducted in 20th century Lebanon. The Christian majority of Lebanon was still there but it showed a long-term trend towards a Muslim majority in the country. This future majority was, however, split and stymied between Sunnis and Shiites. Ultimately then, Lebanon “was fated not to have a majority community” and politics became dominated by the struggles between and within sectarian communities.46

Prelude To Complications In Foreign Policy

An illustrative example of how Lebanon's existential anxieties and sectarian divisions shaped its foreign policy can be found in the government’s response to the British Peel Commission’s 1937 partition plan for Mandatory Palestine. This plan, which was ultimately shelved, would divide Mandatory Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab one, with an international zone remaining under British control. Then-Lebanese President Emile Eddy enthusiastically endorsed the plan. On the very day the report was published, he met with Chaim Weizmann, a prominent Zionist leader and future president of Israel, in Paris, where he raised a toast, saying: “Now that the Peel report is an official document, I have the honor of congratulating the first president of the future Jewish state!” Eddy’s Zionist sympathies were rooted in his belief that a Jewish state could serve as a regional ally to Christian Lebanon and a bulwark against Muslim political ascendancy. In a similar vein, a Maronite patriarch also sent a private message of congratulations to Weizmann, but asked the Zionist leader not to divulge its contents lest Lebanese “Christians suffer a “massacre” if these sentiments were to become known.”47 Thus, even in matters of foreign policy, Lebanon’s deep-seated ideological rifts and sectarian calculations could not be disentangled from the country’s official posture.

The National Pact and Economic Model of Free Lebanon

In 1943, the Maronite and Sunni factions in Lebanon responded to the country’s internal divisions by creating the National Pact, an unwritten power-sharing agreement that both reaffirmed and amended the multi-confessional nature of the emerging Lebanese polity. The general thrust of the pact was that the president of the republic would be a Maronite Christian, the premiership would be retained by a Sunni Muslim, and required that the speaker of the National Assembly be a Shiite.48 They also agreed that Lebanon would be “open to the West,” while acknowledging that it “was part of the Arab world.” This arrangement, which produced a deregulated and more capitalist economy and prohibited an economic union with the Arab world, suited “the business interests of the Christian and Sunni Muslim elite of Beirut.”49 This vision of a laissez-faire democratic free Lebanon that was open to the world was encapsulated in the notion of the country as a Merchant Republic.50

The problem with these political and economic agreements is that they had “time bombs” that were set to go off at some point. The pact was based on the 1932 census, and the political structure was informally anchored to this census, which, over time, became less and less reflective of Lebanon’s actual demographic composition. The Christian claim to their number of seats in parliament and their share of the executive branch became reliant on “fictional demography.” The Christians were at best reduced to demographic parity in Lebanon already by the 1940s and the Sunnis grumbled in the 1943 parliamentary elections that a new census was needed. The Christians, in order to maintain their privileged political position, refused. Economically, the vision of the country as a Merchant Republic set up the conditions for economy to become prosperous.

Into the 1950s, Lebanon’s free market, minimalist state, and strong currency made Beirut the Middle Eastern hub of banking and financial services. Lebanon stood out against the global trend toward restrictive markets and state intervention…With surging oil revenues for the Arabs of the Persian Gulf and capital flight to Beirut as Egypt, Syria, and Iraq shifted to dirigisme from the late 1950s, Lebanon’s financial sector thrived. Between 1949 and 1957, the Lebanese economy grew at more than 7 percent per annum on constant 1950 prices.51

This success had its price as Lebanon’s industry languished, and many Sunnis, Druze, and even rural Maronites did not fully share in the prosperity unleashed by the free market.52 The full effect of these political and economic policies was, however, still to be felt in the future. Lebanon was still in the final movement toward formal independence.

Independent Lebanon: 1946-1975

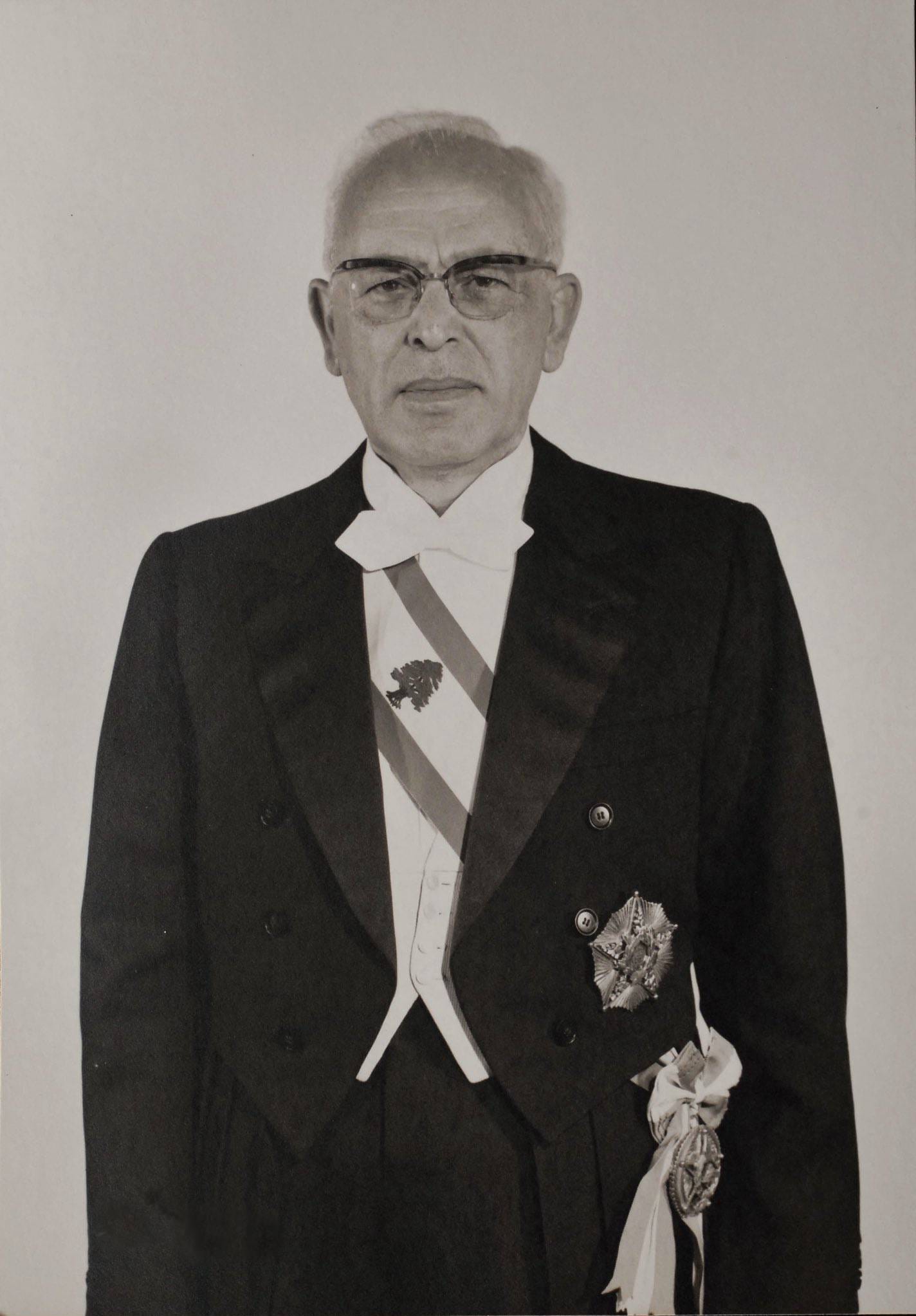

The Mandate for Lebanon officially ended in 1946, ushering in a new era of formal independence.53 In the following year’s parliamentary elections, incumbent President Bechara al-Khuri's position was reaffirmed, despite the presence of electoral “manipulation and irregularities,” as he sought to amend the constitution to allow consecutive presidential terms. At the same time, the crisis in the British Mandate of Palestine and the Arab states’ rejection of the United Nations-sponsored (UN) partition plan offered a timely distraction and, arguably, a convenient pretext for al-Khuri’s constitutional ambitions.54 The 1947 UN Partition Resolution, and the resulting regional fallout, marked the nascent republic's first significant foreign policy crisis. In many respects, it also served as an ominous preview of Lebanon’s internal fragility and susceptibility to external influences in the post-independence era.

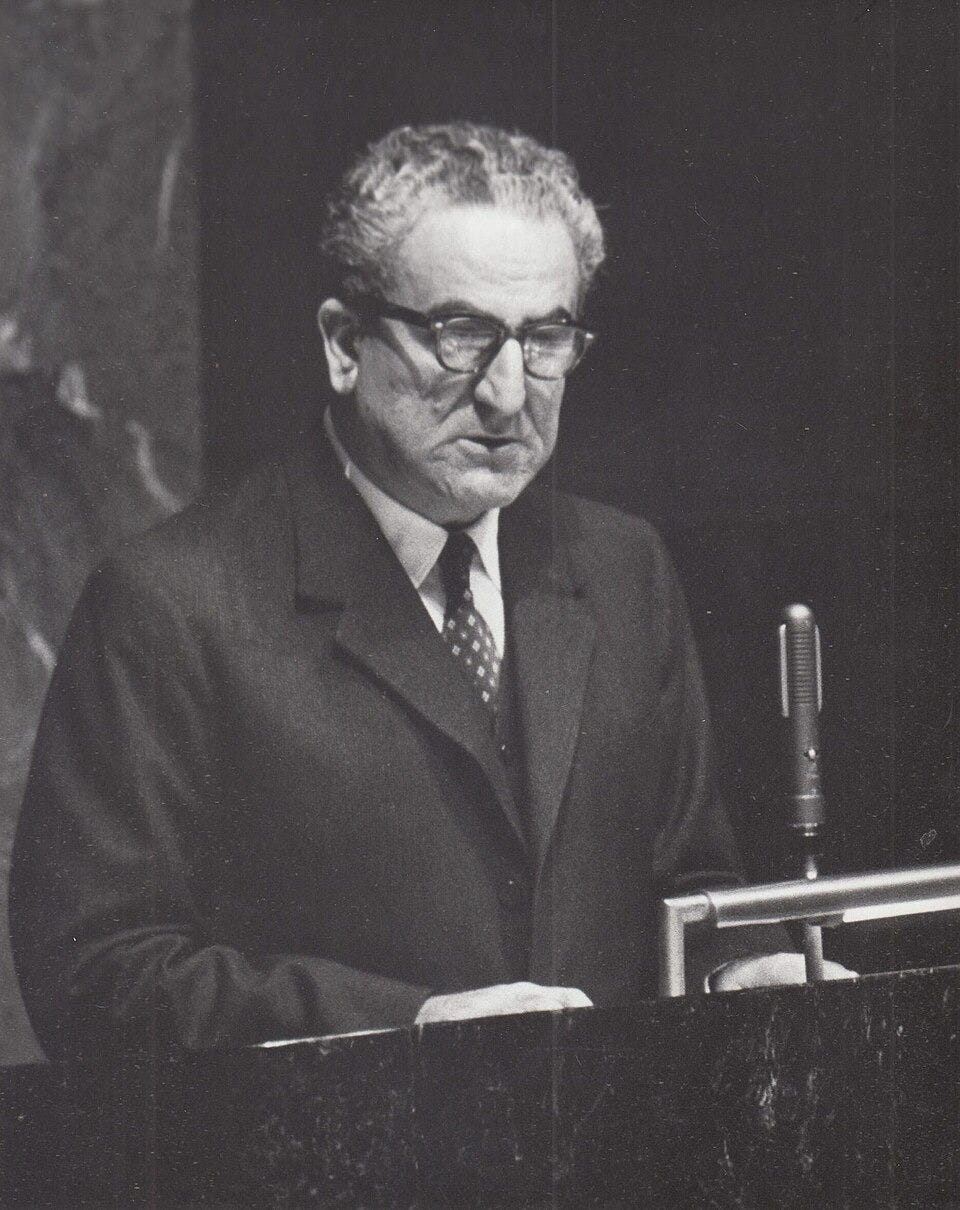

Charles Malik, Lebanon’s youthful and intellectual envoy to the United Nations,55 exemplified the complexities of Lebanon’s foreign policy, which sought to navigate a delicate balance between the Islamic East and the Christian West. Though personally conflicted, Malik ultimately voted against the 1947 UN Partition Plan, reflecting both domestic pressures and Lebanon’s vulnerable regional position.56 When the resolution passed regardless, Malik rose and solemnly quoted the prolific Psalmist, King David: “If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, may my right hand forget its cunning.” The moment was met with a sharp and elegant retort from Abba Eban, the Jewish Agency’s representative: “If you continue saying this for 2,000 years, we shall start believing it.”57 This symbolic exchange captured the underlying tension not only between Zionism and Arab nationalism, but also between Lebanon’s own competing cultural identities and its role in the emerging post-Mandate order.

Unlike much of the Arab world, which regarded Israel as illegitimate from the outset, Malik held a more nuanced view. He feared that Israel might rival Lebanon’s unique position as a cultural and political bridge to the West. Malik publicly maintained that Lebanon, rooted in both the Islamic East and the Christian West “on the footing of equality,” was uniquely suited to act as an arbiter between civilizations. He argued that Israel, by virtue of its Jewish identity, stood outside both spheres and, as such, could not fulfill the same role. He continued to assert this position even when challenged with the argument that Judaism was the root of both Islam and Christianity, suggesting that Israel might also hold value in this intermediary framework.58

Privately, however, Malik “defined Lebanon as a Western Christian state” rather than as a bridge between the East and West.59 Unlike many Arab delegates, he neither boycotted nor avoided interactions with Zionist officials or Jewish representatives, even after his vote to internationalize Jerusalem. As historian Martin Kramer has noted, Malik possessed “a more profound understanding of the historical forces that produced Israel than any Arab in his generation.”

Kramer urges readers to examine Malik’s dispatches from Washington between 1947 and 1949, calling them “prophetic.” Malik never shunned Israeli diplomats or journalists, even in the 1950s and certainly not after 1975. To him, Israel was a political reality Lebanon would have to accommodate—and one he came to respect for its military and scientific achievements.60 Malik’s pragmatic and relatively open stance toward Israel was unusual among Arab politicians at the time. Notably, Malik’s political bloc, the Lebanese Front, would later go so far as to align with Israel.61 Yet, despite these nuanced feelings about Israel, Lebanon would find itself trying to navigate hostile Arab reaction to its founding.

The 1948 War and its Refugee Legacy

Despite the sectarian ambiguity over Israel’s founding, President al-Khouri thought that an easy Arab victory against the nascent Jewish state was assured. He also exploited the crisis to persuade parliament to extend his presidential term. Consequently, Lebanon entered the war on the Arab side, but delegated most of the actual fighting to its native-born son, Fawzi al-Qa‘uqji, and his irregulars.62During the war, around 100,000 Palestinian Arabs63 fled to southern Lebanon where President al-Khouri “rushed to visit” one contingent from Haifa.64 By October 1948, the Lebanese leadership recognized that the Arabs had lost the war and began advocating for an armistice. Israeli forces soon overran al-Qa’uqji and captured various Lebanese villages on the border sparking panic among Lebanon’s commercial elite that had no more stomach for the war.65

Both the president and prime minister, however, were caught in the dilemma that if they were the first to seek an armistice with the Israelis that they would be seen as traitors to the Arab cause. If they did, they reasonably feared that this would weaken Lebanese prestige in the Arab world. When Egypt was the first Arab state to sue and conclude an armistice, Lebanon quickly leaped to be the next state to come to terms with the Israelis.66 The talks between the two sides were, according to the eminent Israeli history Benny Morris, a quick and relatively smooth affair. The talks were characterized by a “friendly atmosphere,” with the Israeli delegation noting that the Lebanese side claimed “that they are not Arabs and that they were dragged into the adventure…against their will. They maintain that, for internal reasons, they cannot openly admit their hatred for the Syrians.”67 The parties signed an armistice agreement on March 23, 1949—a just three weeks after talks began.68

Yet, for all the friendliness and shared concerns, the war had introduced yet another time bomb set to explode from Lebanon and reach Israel. The Palestinian Arabs—predominantly Sunni—became yet another demographic within the rich but tenuous tapestry of Lebanese society. The fact that Lebanon effectively prevented and still prevents this displaced Arabs from en masse assimilating into general society69 would create ripe conditions for mass radicalization among these refugees. But these things are still in the future.

For now, Lebanon was at peace and was prospering. It avoided the coups that were so prevalent in Egypt, Iraq, and Syria at the time. Due to its neutrality and booming economy, Lebanon was hailed as the Switzerland of the Middle East. Beirut, for its promise and beauty, was similarly touted as the Paris of the Middle East.70 The Arab boycott of Israel made Beirut and Tripoli, two cities in Lebanon, the terminus “for piped Saudi oil” and for the Iraq Petroleum Company. Lebanon profited from the flight of Jews from the Arab world to Israel. The upper-class emigration of old Arab elites fleeing radical republican regimes that displaced them to Lebanon similarly benefited the economy.71 The economy boomed, albeit unevenly, and while growth lifted the general population, its greatest returns were skewed toward the Christian middle class.72 Though there were demands by a Sunni Muslim organization for a new census and denunciation of disproportion Christian influence in the country in 1953,73 things were on the surface fairly serene.

The 1958 Dress Rehearsal: Buildup, Activation, And Resolution

The trouble first started from Egypt. A new president determined to make his mark on history and unify the Arabs rose to power in 1954 promising to end the old colonial influence in the Middle East and confront the conservative Arab regimes. This man, Gamal Abdul Nasser, would turn to the Soviet for the arms to carry out his dreams. The Suez Crisis of 1956 would make the charismatic Nasser a household name in the Arab world and the effects of his revolutionary, socialistic appeal would be felt even in bourgeoise Lebanon. President Camille Chamoun, a graduate of Saint Joseph, fear of the Egyptian dictator and his pro-Western sentiments moved him to refrain from cutting ties to Britain and France during the 1956 crisis. For this refusal, his Arabist prime minister resigned, Radio Cairo and Lebanese Nasserites denounced him. His new government included the pro-Western Charles Malik as foreign minister and those non-Christians who shared his misgivings about “Nasser’s influence on Lebanese Muslims.”74

Lebanon proved to be “the only Arab country” to accept U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower offer to provide military assistance to any state in the region facing “armed aggression” from a communist supported state.75 Chamoun felt that the local Sunni support for Nasser as well as Egyptian and Syrian financing of his opponents violated the National Pact’s pledge to keep Lebanon aloof from such regional intrigues. By the June 1957 parliamentary elections, the Americans were financing Chamoun and his supporters. A failed coup sponsored by the U.S. in Syria later that year caused Syria and Egypt to enter into a short-lived political union. The Egyptians then started to “fed weaponry across the Syrian/Lebanese border” to the opposition. An assassination of a Maronite opposition newspaper editor led to the opposition military mobilizing and violence breaking out in blurred sectarian fashion in 1958. Civil war loomed large. Chamoun and the government appealed to Eisenhower to intervene. Egypt then suddenly ended its military support for the rebels. The United States, Egypt, and Lebanon hammered out an agreement. Chamoun would not seek re-election and he would be succeeded by Fuad Shihab, the chief of staff of the army76—a Maronite-dominated institution.77 The U.S. briefly landed 14,000 troops in the country and mediated between the factions to ensure tranquility and a peaceful transfer of power.78 This crisis would be but a dress rehearsal for much larger catastrophic civil war to come almost two decades later.

1967 Six Day War And The New Arab Left Rising

While Lebanon would avoid the pitfall of joining the Arab coalition against Israel in 1967, the Six Day War changed the mood of the Middle East. Many illusions went up in smoke including the previously held belief that the West and its allies were on the decline and that the Third World was fated to rise.79 A sledgehammer blow was dealt in six short days of war to the idea that the Marxist and Arab revolution against Israel and the West was to be inevitably triumphant.80 The old idol Nasser was tarnished though he managed to cling to power until his death. His cause of Pan-Arabism was dealt a fatal setback. So too was the confidence of the Arab world. Shame and disorientation reigned supreme among Arab intelligentsia causing fragmentation.

The unity between Arab nationalism and Marxism, which was once asserted by many intellectuals, was dissolved. Nasserism was discredited, Baathism split between Syria and Iraq. The Palestinians started their own revolution inside the revolution. Eventually, the Arab left split into three new circles: The old left, the new left, and the Islamic left leading a revolution against the revolution.81

Arab unity was dead, but Marxism still lived. It would be wrong to claim that the origin of these divisions and disputations emerged ex nihilo from Israel’s triumphant war against a coalition of Arab states alone.

Indeed, Mansour noted that some intellectuals began questioning Nasser’s place in the Arab world dating back to his failed union with Syria that broke up in 1961. This process was slow and gradual until the Six Day War allowed these seeds to suddenly flourish and sprout. The timing of its sudden release was fortuitous given that it “coincided with the rise of a new cultural radicalism and a New Left internationally.”82 This new Arab left— its secular, Palestinian, and religious components—would have repercussions for Lebanon.

Though the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), established in 1964 to represent all Palestinian factions, was already using Lebanon for military training,83 the aftermath Six Day War diminished the Lebanese state’s ability to curb the power and the militancy of the organization. The PLO in 1968 began using Lebanon as a launching pad for attacks on Israel—even when it led toward retaliatory strikes by the Lebanese army and the Israeli army.84

A Lebanese attempt to crack down on PLO in 1969 caused the Lebanese Left to move from protests to outright clashes with authorities. This internal crisis precipitated an external one when Syria closed the border. To relieve the pressure, Lebanon effectively ceded its sovereignty to the PLO by signing the Cairo Agreement to end the crisis. This pact, authored by an ailing Nasser, allowed Yasser Arafat, the leader of the PLO, to construct a state within a state in Lebanon by granting them “military freedom” in Palestinian refugee camps and “access to the border with Israel [to carry out attacks].”85

The Jordanian crackdown on the PLO in 1970-1971 facilitated the flight of thousands of fighters and their families to Lebanon. Arafat, after his expulsion from Amman, made Beirut his homebase.86 The Lebanese left deepened its involvement with the PLO in ways that only undermined the fragile state of peace within the country:

Between mid-1970 and mid-1971, developments titled Lebanon toward unviability, though the implications took time to become apparent. Kamal Jumblat[t], who in April 1969 set his PSP [Progressive Socialist Party] at the head of the National Movement of leftist parties demanding Palestinian freedom of action, took his opportunity as interior minister in the government preceding the August 1970 presidential election to legalize his partners—the Nasserites, Ba’[a]thist, Communists, and the SSNP [the party for Greater Syria founded by Saadah]. The SSNP had shifted in the late 1960s from hard right to hard left. Only the PSP had real public weight, courtesy of Jumblat[t], but all had noteworthy paramilitaries trained by the PLO.87

Suleiman Frangieh would ascend to the presidency during these turbulent times in Lebanese politics.

Frangieh’s election was on the back of a bare majority—literally the one vote cast by Jumblatt determined the victor—between ideologically and demographically contending forces. He promised to be all things—even though these promises were fundamentally contradictory— to all factions. He presented himself as a friend to Syria, an ally to the Left and Palestinians, an upholder of Maronite privileges and Lebanese sovereignty.88 Once elected, he further crippled the state’s capacity to deal with those tearing it apart, alienated Jumblatt, and prevented reforms that addresses socio-economic grievances.

The last elections in 1972 before Lebanon’s eruption to civil war, though deemed “the best organized and most honest," resulted in “[t]hree radical leftists” attaining parliamentary seats.89 Meanwhile, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) intensification of its military operations against Israel, most infamously through the 1972 Munich Olympic massacre, resulted in Israeli reprisals.90 More than a state within a state, the PLO increasingly rivaled the Lebanese government in terms of territorial control and military strength. Its growing power alarmed the president who attempted a crackdown in 1973.

The resulting clashes triggered a regional response: Syria imposed an economic boycott on Lebanon and facilitated the movement of Palestinian fighters across the border. Frangieh was forced to suspend his offensive, and a reassertion of the 1969 Cairo Agreement followed. Though the PLO formally pledged not to use Lebanese territory to launch attacks on Israel, it repeatedly violated this agreement, expanding both its buffer zones and influence—particularly in Beirut.91 Fearing the combined threat of the PLO and the increasingly mobilized Lebanese Left, the Maronite Christian leadership organized its own militias to safeguard sectarian interests, as the Lebanese Army steadily became a fragmented, ineffective, and irrelevant institution.92 The collapse of central authority, the rise of paramilitary forces, and unresolved tensions between Lebanon’s diverse religious and socio-economic communities created the conditions for civil war and for Charles Glass’s lament in his 1989 documentary.

II Kings 19:23

See EclipsedLebanon. (2009, April 19). Pitty the nation-Charles Glass’s Lebanon-Part 01 [Video]. YouTube.

In That Howling Infinite. (2017, June 9). Pity the nation that is full of beliefs and empty of religion. Howlinginfinite.com, WordPress. https://howlinginfinite.com/2017/06/09/pity-the-nation-that-is-full-of-beliefs-and-empty-of-religion/.

EclipsedLebanon. (2009). Pitty the nation, 9:25-9:38.

Phoenicians themselves saw themselves as an extension of the Canaanites after the Bronze Age Collapse. Within the archeological camp of Biblical minimalists there are those like Israel Finkelstein who argue that the Israelites were the same product of the same collapse and that they too were largely descendants of the same Canaanite peoples. There is some genetic evidence that Jews today have some Canaanites ancestry. See Sauter, M. (2024, September 28). Who Were the Phoenicians? Biblical Archeological Society. https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/ancient-cultures/ancient-near-eastern-world/who-were-the-phoenicians/; Tel Aviv University. (2020, June 1). Study finds ancient Canaanites genetically linked to modern populations. Biblical Archeological Society. https://english.tau.ac.il/news/canaanites; Wallace, J. (2006). Shifting Ground in the Holy Land. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/shifting-ground-in-the-holy-land-114897288/.

Indeed, many of the old timer Anglo missionaries referred to Lebanon as “the Lebanon” and saw it not so much as its own independent polity but as an extension of Syria.

Kaplan, R.D. (1993). The Arabists: The Romance of an American Elite. The Free Press, 26.

Ibid., 27.

Ibid., 28.

Ibid., 27. Political scholars Azar Gat and Alexander Yakobson posit that various confessional communities—such as the Greek and Syrian Orthodox that did not fully adopt the Arab identity were in reality as much ethnic as religious communities. These elements attained some form of recognition in the Ottoman millet system. See Gat, A. & Yakobson, A. (2013). Nations: The Long History and Deep Roots of Political Ethnicity and Nationalism. Cambridge University Press, 123-125. In light of this, Kaplan’s analysis about animosity between the Protestant Anglos and the Greek Orthodox and Maronites may have also had ethnic origins as well.

Kaplan, R.D. (1993). The Arabists, 33.

Ibid., 34.

Ibid., 35.

Ibid., 34-35.

Ibid., 37.

Now it is known as the Saint Joseph University of Beirut.

Kaplan, R.D. (1993). The Arabists, 37-38.

For Azouri’s origins, see Rubin, B.R. (2023, October 24). The Janus-faced undergirding the Israel-Gaza conflict. Responsible Statecraft. https://responsiblestatecraft.org/israel-gaza-public-opinion/.

Laqueur, W. & Schufetan, D. (Eds.). (2016). The Israel-Arab Reader: A Documentary History of the Middle East Conflict (8th ed.). Penguin House, 10. In history’s ironic twists, Egypt today formally identifies itself as an Arab country and is a leading Arab power.

See echoes of this sense of Lebanon as a continuation of Phoenician civilization in Franck Salameh. (2023, January 24). Episode 37, Is Lebanon Kaput? [Video]. YouTube.

; Franck Salameh (2023, April 11). Episode 39, Lebanon is Phoenicia [Video]. YouTube.

.

This is the belief that all Arab majority states and peoples should be consolidated under one state.

This is the belief that Syria should include not just present modern-day Syria but also all of Israel, Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, and Lebanon. It can also include Cyprus as well as bits of Iran, Egypt, and Turkey.

Harris, W. (2012). Lebanon: A History 600-2011. Oxford University Press, 174-176.

Ibid., 175.

Ibid.

Ibid., 176.

Such promises were made in the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence, see https://spot.colorado.edu/~gyoung/home/IA%201000/Course%20Readings/McMahon_Hussein.pdf. France would still toy with handing over to Faisal as part of his promised Syrian Arab kingdom in exchange for Faisal agreeing to French tutelage but would shelve this idea with the help of the Maronite church and their administrative council. See Harris, W. (2012). Lebanon, 174-175.

Harris, W. (2012). Lebanon, 176-177. Indeed, the violence over Faisal’s ouster by the French would even hit the British Mandate of Palestine. The Arab locals, regarding themselves as southern Syrians, protested French action and tried to assist Faisal. This contributed to the highly charged atmosphere that would result in the 1920 Nebi Musa riots, the first mass violent Arab action against Zionism. On this, see Segev, T. (2000). One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs Under the British Mandate (H. Watzman, Trans.). Holt Paperbacks, 122-133.

Harris, W. (2012). Lebanon, 176.

Ibid., 178.

Ibid.

Ibid., 178-179.

Ibid., 179.

Ibid., 179-180.

Ibid., 180.

Ibid.

Ibid., 182.

Ibid., 183.

Ibid., 184.

Ibid., 181.

On this point see Provence, M. (2005). The Great Syrian Revolt and the Rise of Arab Nationalism. University of Texas Press.

Mansour, H.A. (2022, July 10). The Liberation of Arabs From the Global Left. Tablet Magazine. https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/israel-middle-east/articles/liberation-arabs-global-left.

Ibid.

From Swastikas to Bullets: The SSNP’s Disturbing Journey in Syrian Politics. (2023, July 19). Levant 24. https://levant24.com/articles/2023/07/from-swastikas-to-bullets-the-ssnps-disturbing-journey-in-syrian-politics/. The Ba’athists themselves also had totalitarian affiliations, see Berman, P. (2012, September 13). Baathism: An Obituary. The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/107238/baathism-obituary. In terms of Nazi emigres to Syria, see Solomon, J. (2024, December 19). The Nazi of Damascus. The Free Press.

. Given these ties and affinities is it not surprising that in Bashir Assad’s private photos, there is a photo of him posing with a cousin sporting a T-shirt “emblazoned with an image of Hitler”? See PA News Agency. (2024, December 13). Bizaare personal photos of ousted dictator Assad spark ridicule in Syria. The Herald. https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/national/24795918.bizarre-personal-photos-ousted-dictator-assad-spark-ridicule-syria/

See Encyclopedia Britannica. (n.d.). Anṭūn Saʿādah: Syrian politician. In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved May 2, 2025, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Antun-Saadah

Harris, W. (2012). Lebanon, 185.

Kessler, O. (2023). Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict. Rowman & Littlefield, 100. For more on the relationship between the Maronites and the Zionists from 1920-1948, see Abramson, S. (2012). The Promise and Failure of the Zionist-Maronite Relationship, 1920-1948. [Master thesis, Brandeis University]. https://scholarworks.brandeis.edu/esploro/outputs/graduate/The-Promise-and-Failure-of-the/9923879974001921.

Encyclopedia Brittanica (n.d.). Lebanese National Pact. In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved May 2, 2025, from https://www.britannica.com/event/Lebanese-National-Pact-1943.

Harris, W. (2012). Lebanon, 193.

Rozelier M. & Al-Attar, S. (2019, November 13). From a Merchant Republic to Rentier Capitalism—A Story Of Failure. Le Commerce Du Levant. https://www.lecommercedulevant.com/article/29439-from-a-merchant-republic-to-rentier-capitalism-a-story-of-failure.

Harris, W. (2012). Lebanon, 194.

Ibid., 195.

Barnett, R.D. et al. (n.d.). French mandate in Lebanon in History. In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved May 2, 2025, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Lebanon/French-mandate. To be sure, others make the case that Lebanon became effectively independent in 1943 when she declared independence. But British and French foreign troops only withdrew from the country in 1946.

Harris, W. (2012). Lebanon, 201.

He was a member of the Greek Orthodox church—a Christian sect in Lebanon that comprised 8 percent of the population—and the founder of AUB’s philosophy department. On his life and thought, see Eylon, L. (2022, September 2). Man of the Middle East: Charles Malik. The Times of Israel. https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/man-of-the-middle-east-charles-malik/

Ibid.

See Einhorn, T. (2024, July 2). Israel Under Fire—Israel’s Legal Rights Regarding Settlements. Jerusalem Center for Security and Foreign Affairs. https://jcpa.org/article/israel-under-fire-israels-legal-rights-regarding-settlements/.

The Philos Project. (2024, September 19). Lecture: Charles Malik and Edward Said’s Respective Approaches to the West [Video]. YouTube, 14:43-15:33.

.

Ibid.

Ibid., 16:24-16:57.

Ibid., 16:57-17:02.

Qa’uqji was the head of the Arab Liberation Arab, a group of Palestinian Arab and foreign irregulars, in Israel’s War of Independence. He also was a Nazi supporter and member of the Wehrmacht during the Second World War. See Fawzi al-Qawuqji (1890-1977). (n.d.). Jewish Virtual Library. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/fawzi-al-qawuqji.

Fraser, P.M. et al. (n.d.). Palestine and the Palestinians (1948-1967). In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved May 4, 2025, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Palestine/Resurgence-of-Palestinian-identity.

Harris, W. (2012). Lebanon, 202.

Ibid.

Ibid., 202-203.

Morris, B. (2008). 1948: The First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press, 378.

Ibid., 378-379.

Joffre, T. (2022, February 13). Palestinian professionals banned from work in Lebanon for second time. The Jerusalem Post. https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/article-696289; Maynard, J. (2022, February 18). Apartheid-like situation of Palestinians in Lebanon reasserted—no-one notices. AIJAC. https://aijac.org.au/fresh-air/apartheid-like-situation-of-palestinians-in-lebanon-reasserted-no-one-notices/; Najdeh Association et al. (n.d.). UPR 2020: Palestinian Refugee Rights in Lebanon. United Nations Human Rights Council.

Narayan, P. (2024, September 24). Lebanon: How Switzerland of Middle East became modern-day nightmare. India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/world/story/lebanon-paris-of-middle-east-modern-day-nightmare-economic-crisis-hezbollah-israel-beirut-night-club-party-2605518-2024-09-24.

Harris, W. (2012). Lebanon, 202.

Ibid., 208.

Ibid., 209.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid., 210-212.

The chief of staff is a position reserved for a Maronite officer. See Jangadost, M. (2025, March 13). Lebanon Appoints Rodolphe Haikal as Army Commander Amid Security And Economic Challenges. Channel 8. https://channel8.com/english/33857.

Harris, W. (2012). Lebanon, 212.

Mansour, H.A. (2024, March 13). The Myth of the “Arab-Israel Conflict.” The Abrahamic Metacritique, Substack.

.

Mansour, H.A. (2022, July 10). The Liberation of the Arabs.

Ibid.

Mansour, H.A. (2024, July 14). Arabs After Defeat: Revolution Inside the Revolution. The Abrahamic Metacritique, Substack.

.

Harris, W. (2012). Lebanon, 220.

Ibid., 222.

Ibid.

Ibid., 223-224.

Ibid., 223.

Ibid.

Ibid., 224.

Ibid., 225.

Ibid, 225-226. For one of these cross-border raids by Palestinian terrorists that violated the pledge, see Kuttler, H. (2024, May 13). The Legacy of the Maalot Massacre. Tablet Magazine. https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/community/articles/maalot-massacre-fifty-years-terrorist-attack-israel. By terrorist, I mean an organization that would explicitly target civilian centers —even that of a school—to inflict death and damage for political purposes. I do not just mean violent anti-governmental activities.

Harris, W. (2012). Lebanon, 225-226.